At first the narrator of “The Consultant,” the opening story of Catherynne M. Valente’s excellent new collection The Bread We Eat in Dreams, sounds like your standard, tired Raymond Chandler private investigator:

She walks into my life legs first, a long drink of water in the desert of my thirties. Her shoes are red; her eyes are green. She’s an Italian flag in occupied territory, and I fall for her like Paris. She mixes my metaphors like a martini and serves up my heart tartare. They all do. Every time. They have to. It’s that kind of story.

But before you get the chance to roll your eyes and maybe double-check that you are in fact holding the right book, things right themselves. The dame explains her troubles, and it soon becomes clear that this is not your standard noir P.I.:

I’m not so much an investigator as what you might call a consultant. Step right up; show me your life. I’ll show you the story you’re in. Nothing more important in this world, kid. Figure that out and you’re halfway out of the dark.

Call them fairy tales, if that makes you feel better. If you call them fairy tales, then you don’t have to believe you’re in one.

I believe it’s no coincidence that this story was chosen to open Catherynne M. Valente’s new collection The Bread We Eat in Dreams. It feels suspiciously like a mission statement of sorts. “Here’s where we’re going with these stories, folks. Get ready.”

In the (copious, wonderful, revelatory) story notes included in this collection, Valente repeats a few ideas that pop up in several of these stories and, looking further back, all across much of her previous output.

The first one of these, and the one “The Consultant” directly addresses, is the power of the fairy tale and the myth, how they are “real life, no different, no better and no worse, and how there is power to be found there, both in telling the tale and having it told to you.”

The second idea, and something she mentions several times in this collection’s story notes alone, may seem contradictory to the first one: “I always want everything to Have Been Real. Prester John’s kingdom, fairy tale creatures, the physics of the classical world.”

So are they real or not? Yes? No? Both, maybe. It’s the telling of the story that keeps the story going. It’s the repeating of the pattern that lays bare the fact that it was always there, all along, and will be there after the story ends. After we’re gone. It keeps going. It keeps us going.

What Catherynne M. Valente does better than, I think, almost anyone else in the genre today, is showing those underlying story patterns, cross-referencing them across cultures and historical periods and, for want of a better word, issues. At their best, her stories make you recognize their foundations and amplify their effect by pulling them, respectfully but firmly, into a modern narrative sensibility.

See, for example, “White Lines on a Green Field,” which is something like Teen Wolf meets Friday Night Lights, except Teen Wolf is the trickster Coyote, who plays QB for the Devils and has a thing with a girl called, yes, Bunny. When they play the LaGrange Cowboys, he says “I got a history with Cowboys.” Yeah.

Or, picking another random example, “A Voice Like a Hole,” about Fig, a teenage runaway whose nickname derives from an apocryphal Shakespeare fairy:

See, in eighth grade, my school did Midsummer Night’s Dream and for some reason Billy Shakes didn’t write that thing for fifty over-stimulated thirteen-year-olds, so once all the parts were cast, the talent-free got to be non-speaking fairies.

And yes, there was a stepmother, before she ran away:

She’s just a big fist , and you’re just weak and small. In a story, if you have a stepmother, then you’re special. Hell, you’re the protagonist. A stepmother means you’re strong and beautiful and innocent, and you can survive her—just long enough until shit gets real and candy houses and glass coffins start turning up. There’s no tale where the stepmother just crushes her daughter to death and that’s the end. But I didn’t live in a story and I had to go or it was going to be over for me.

I’ll let you ponder the layers of a story with a girl named after a non-existent A Midsummer Night’s Dream fairy saying it’s going to go badly for her because she’s not in a story. It’s really only the kickoff point for a gorgeous, moving piece of fantasy literature.

One of my favorites in this collection, although it took a little bit of research before I more or less got what Valente was doing here, is “We Without Us Were Shadows.” It’s a story about the Brontë siblings, all four of them, and the way they used to write elaborate, collaborative fantasy stories and poems set in crazily complex imaginary worlds. Valente takes this idea and sort of Moebius-strips it around to something truly special. Digging into why this story is so brilliant would probably need a separate post in itself. (Do some basic Googling about Angria and Gondal and the early lives of the Brontës if you’re not familiar. The actual history is utterly wonderful in itself, and being aware of it will make this story shine.)

Further on in the collection, you’ll find two powerful novellas, Fade to White and Silently and Very Fast. These are so different from anything else in the collection (and from each other) that it really drives home the point Lev Grossman once made to me about Valente in an interview: “there is nothing she can’t do with words.” So, briefly about these novellas:

Fade to White is something like an alternate history gender dystopia, set in a U.S. that lost (or, more accurately, is still losing) World War II. Large parts of the country have been nuked. Joseph McCarthy is President with Ray Kroc as VP. In order to keep the population numbers up, there’s an institutionalized forced-marriage system, although one that’s very different from what you’d maybe expect. (Hint: dads are encouraged to register for Father’s Day presents to avoid getting duplicate gifts.)

The novella intertwines the stories of young people who are about to enter this system with a series of notes on pitches for TV commercials that are blackly hilarious in the way they illustrate the world and try to put a positive spin on this broken society. (There are tons of examples in the actual stories too—see, for example, a throwaway reference to a breed of chicken called Sacramento Clouds, because they’re huge and orange and radioactive.)

I can imagine Valente setting out to write Fade to White and sort of gritting her teeth, mumbling “I’m going to out-dystopia ALL dystopias with this one.” It’s shockingly harsh, one of the darkest stories I’ve ever read, and simply unforgettable.

And then there’s Silently and Very Fast, the story of Elefsis, a far-future AI shown across the ages and generations of the family that created it. Elefsis grows from a basic house management routine to, well, you’ll see. It deals with machine intelligence in a way that’s quite unlike anything I’ve read in SF.

It’s an extremely dense little novella, hard to appreciate fully on a first reading because it’s so jam-packed with concepts and characters. In the notes Valente explains how it was originally planned to be a novel, and for my taste, as critically acclaimed as this story is, I feel that it maybe would have worked better in a longer format, if only because I wanted to read more about the human characters.

As it is, we see the story at the speed of a wholly unique artificial mind: lives flash by while its awareness grows. It reinforces a point briefly made during the narrative: is it unfair to require such a being to pass a Turing test to prove its worth? The test is a human concept—does this put the onus unfairly on a testee whose consciousness is inherently different?

The funny thing about both of these novellas is that they still contain that same thread of mythology and folklore, if less overtly. They still show how rituals create structure in life and help project it into the future. In Fade to White the symbolism is harsh and direct: the gospel of “pseudo-Matthew” used to manipulate the populace is as cynical as anything Valente has written. In Silently and Very Fast, as much as it may be grounded in hard science, the story of the AI who gained self-awareness and overthrew and enslaved its human masters is tellingly called a “folk tale,” and Elefsis itself develops on a diet of fairy tales. As one of its human owners (companions? progenitors?) says:

“I’ve been telling it stories. Fairy tales, mostly. I thought it should learn about narrative, because most of the frames available to us run on some kind of narrative drive, and besides, everything has a narrative, really, and if you don’t understand a story and relate to it, figure out how you fit inside it, you’re not really alive at all.”

The recognizability of Valente’s sources is one of the main reasons why many of these stories (and poems, for that matter) work so well. You don’t have to be a literary scholar to enjoy poems like “Mouse Koan” or “What The Dragon Said: A Love Story.” You know these icons, you know these stories, and so you can appreciate the artistry of Valente’s writing and her dazzling conceptual acrobatics without worrying that you’re missing some basic underlying bit of esoteric knowledge. (And the story notes are there to point the way otherwise, as with the Brontë story I mentioned earlier.)

Another example of this, by the way, is Valente’s brilliant novella Six-Gun Snow White, possibly my favorite work of fantasy published in 2013. Snow White in the Wild West: there’s a certain comfort in recognizing those elements. Six-Gun Snow White is not included in this collection, but one story and one poem that are somewhat connected to it are: “The Shoot-Out at Burnt Corn Ranch over the Bride of the World” and “The Secret of Being a Cowboy”.

It’s impossible to give each of these stories the attention they deserve. There are brilliant conceptual exercises like “Aeromaus,” sweet contemplations on ritual like “The Wedding” and “Twenty-Five Facts about Santa Claus,”and the confession-like emotional wallop of “The Red Girl.” The range Valente demonstrates across The Bread We Eat in Dreams is truly astounding.

Even comparing simple images (e.g. the “Sea of Glass” from Fade to White and the “Glass Town” from “We Without Us Were Shadows”) can send you down a deep rabbit-hole. “The Girl Who Ruled Fairyland—For a Little While” contains so many ideas both familiar (at the World’s Foul—not Fair, mind you: “Lamia’s Kissing Booth, No Refund!”) and weird (the Carriageless Horse!) that every sentence becomes a wonder.

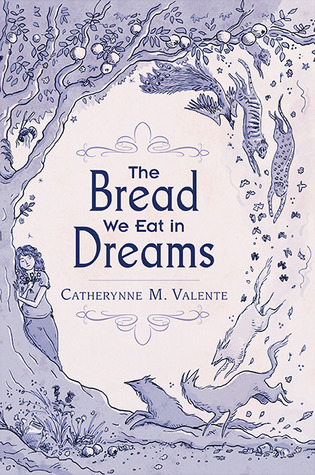

I love this collection. I love how Valente consistently delivers the most gorgeous prose to be found in the genre. I love how she avoids using myth and folklore as mere tools, but instead incorporates them as naturally as breathing, bringing all their layers of meaning into play without diminishing their power. She seems to be able to do everything: fairytale, far-future SF, contemporary fantasy, bleak dystopia, poetry. Add to this a lovely cover and wonderfully appropriate interior illustrations by Kathleen Jennings, and you end up with The Bread We Eat in Dreams: a collection for the ages. Don’t miss it.

The Bread We Eat in Dreams is available now from Subterranean Press.

Stefan Raets reads and reviews science fiction and fantasy whenever he isn’t distracted by less important things like eating and sleeping. You can find him on Twitter, and his website is Far Beyond Reality.

“Fade to White” was a nominee for the 2012 Sidewise Award for Alt History; it certainly was my choice among the nominated stories. The gut punches just keep coming as the story is unpacked, like realizing just who is presenting those ghastly TV commercial pitches.